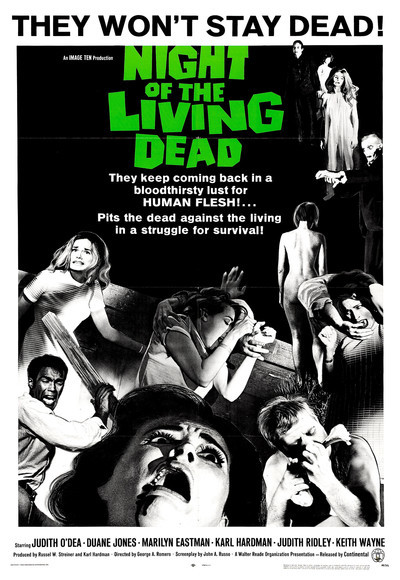

US | 1968 | Directed by George Romero

Logline: A ragtag group of men and women barricade themselves inside a farmhouse in an effort to stay safe from a plague of cannibalistic walking dead.

George A. Romero pioneered what we appreciate as the modern horror movie with this seminal, unconventional shocker. Shot on 16mm, in grainy black and white, on the smell of an oily rag, with a bunch of amateur actors, in and around his then hometown of Pittsburgh. The movie became a staple of the burgeoning midnight movie circuit, spawned a worldwide cinematic phenomenon known as the zombie apocalypse, and went on to earn the director the crown of Godfather of the Dead.

Along with William Friedkin’s The Exorcist and Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Night of the Living Dead re-vitalised a dying art form, injecting it with a dark, uncompromising attitude, and giving it the visceral, nihilistic edge it so demanded. It was the beginning of the end of Hammer Horror’s soft grip, and while Euro darling Roman Polanski delivered a mainstream hit with Rosemary’s Baby, the subversive sideshow shadow of Hollywood exploded in all its glorious grotesquerie.

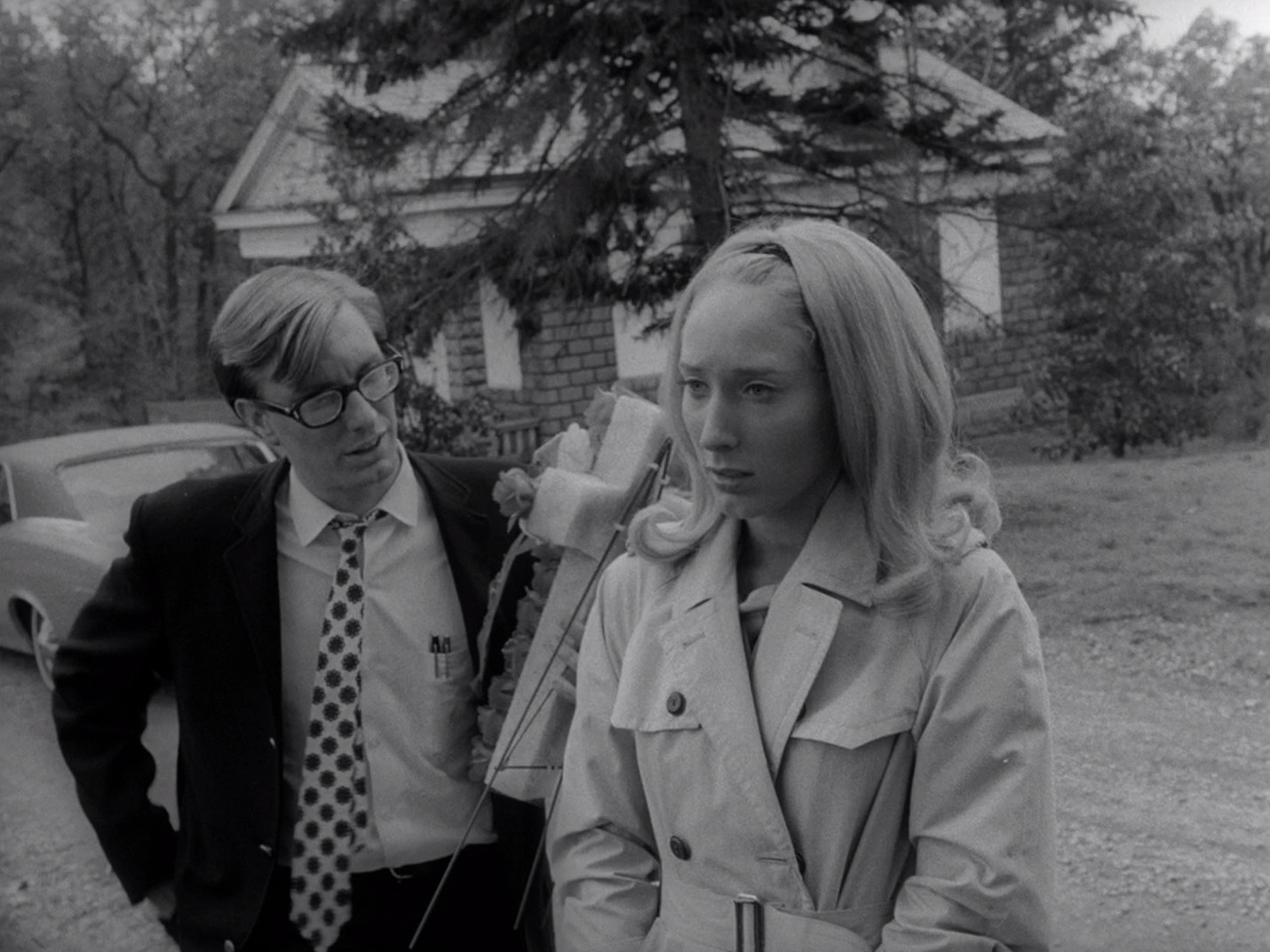

A young man, Johnny (Russell Streiner), and his sister Barbara (Judith O’Dea), are visiting their parents grave when they are terrorised by a tall, shuffling, seemingly deranged, and rather ghoulish man. Johnny has been teasing Barbara, “They’re comin’ to get you, Barbara! Look there’s one of them now!” But, the ghoul fatally wounds Johnny, and Barbara just manages to escape.

She seeks shelter in a nearby farmhouse where she discovers several others already hiding out. It becomes quickly apparent that the countryside is running amok with those things, what we now call “zombies”; the dead have come back to life and have only one desire: to eat living human flesh. Anyone bitten by one of the ghouls becomes a ghoul. The only way to kill them is to destroy the brain.

Ben (Duane Jones) seems the only one of the household with any shrewdness and ingenuity, the others; a married couple Harry (Karl Hardman) and Helen Cooper (Marilyn Eastman) and their young daughter Karen (Kyra Schon), Judy (Judith Riley) and Tom (Keith Wayne), and heavily traumatised Barbara, are all rather hopeless.

The screenplay was co-written with John Russo, who had a falling out with Romero after the movie’s success, and in their subsequent legal settlement Romero wasn’t allowed to use the words “Living Dead” in any sequels he might wish to make. The script is lean and mean, with strongly etched characters, and surprisingly realistic dialogue. But most effective of all is the movie’s savage, uncompromising denouement. It’s Murphy’s Law through and through, the most bitter of ironies, with the end credits playing over a montage of images that gives the movie a docu-drama authenticity.

The handheld camerawork - shot in Academy ratio - adds a claustrophobic urgency to the film’s visual narrative. Romero was the uncredited cinematographer, and co-editor (along with Russo). The clever use of having most of the graphic violence occur in shadows or half-light only intensifies the tenebrous, nightmare atmosphere. The scene when Ben first discovers a body with its partially-eaten face on the staircase of the farmhouse is a genuinely alarming image; it’s mostly in shadow, but the staring dead eye and ruined flesh makes for a truly horrific motif for the whole film.

Night of the Living Dead is an excellent example of DIY, indie filmmaking. Despite the supernatural, almost absurd premise the movie is presented as realistically as possible. Imagine the genuine shock audiences would’ve had seeing this on the big screen almost fifty years ago. The atmosphere is so palpable, and the pacing brisk, you forget the movie’s technical limitations and goofs. Romero has always been fantastic at paring everything back to the essential elements of cinematic storytelling, and Night of the Living Dead is fully deserving of its enduring cult classic status in every way.