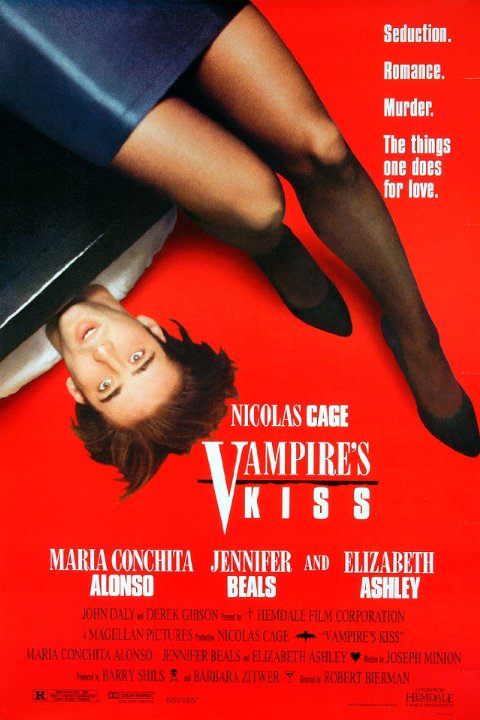

USA | 1989 | Directed by Robert Bierman

Logline: A Manhattanite publishing executive is visited and bitten by an apparent vampire, a woman he previously slept with, and he starts to exhibit erratic and obnoxious behavior.

One typical night while Peter Loew (Nicolas Cage) is having drinks with colleagues he meets sexy Rachel (Jennifer Beals). He invites her back to his place (bad idea, but he’s none the wiser) and they neck furiously. To be precise, it’s Rachel who necks Peter. The next morning Peter brings her coffee, but Rachel isn’t there. Has Peter imagined her?

Vampire’s Kiss is a weird little movie and brilliant. The screenplay is by Joseph Minion, who also penned another blackly comic, sly tale of urban paranoia: Martin Scorsese’s After Hours. Any comedy that deals with schizophrenia, sexual assault, and murder, is most definitely of a darker hue, and right up my twisted little alley! It also features one of the most mannered performances in Nicolas Cage’s career (the fake pretentious accent alone is eccentric comedy gold!), and yes, that's saying a lot.

Bierman caresses the Big Apple affectionately, even obsessively; the opening establishing montage slyly focuses on the city’s spired skyscrapers; the Empire, the Chrysler, and other inverted architectural “fangs”. There is a sub-text at play about the stresses of modern city life, which the vampire’s curse uses this to great metaphorical effect. Rachel’s vamp is very much the classic femme fatale, and New York City is renowned for encouraging any kind of outlandish public behaviour, or at the very least it is ignored by the locals; so Lowe’s slide into madness is water off his therapist, Dr. Glazer (Elizabeth Ashley)'s back.

It is Loew’s targeting of work colleague Alva (Maria Conchita Alonzo) – “Am I getting tha-roo to you Alva!” – that laces the tale with genuine discomfort, and Loew’s fantasy world colliding with reality that provides the movie with much of its inspired satire. Along with the corporate realm, the classic vampirism elements are mercilessly teased and manipulated; the bat in Loew’s apartment, the sun hurting his eyes, his ruthless arrogance at work, and his desire to act subversively at night whilst dressed in a suit and tie (his undead strut through a packed nightclub dancefloor is yet another example of the movie's marvelous off-kilter humour).

The copper-tinged sensibilities of this corrupt bloodsucker are an acquired taste, but like most movies that feature on this page, it gets better with each viewing. There is much to relish, especially some of the eccentric asides; the mime artists outside Loew’s brownstone, the elderly woman cussing in the office bathrooms, Loew using his upturned sofa as a “coffin”, Loew pulling faces as he runs amok with plastic fangs, and of course, Cage’s haircut and his method acting (infamously he plucks and actually chows down on a real cockroach!)

Not only is Vampire’s Kiss one of my favourite vampire movies, but I firmly stake that it is also one of Cage's finest performances, and the most bitingly-funny comedies of the 80s, up there with the very best of those that have a cumulative effect.