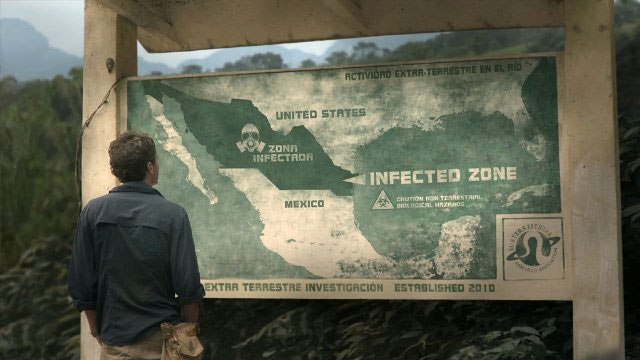

2010 | USA | Directed by Gareth Edwards

Logline: After a returning space probe has inadvertently deposited alien organisms on Earth, a journalist reluctantly agrees to escort a tourist through the infected zone to safety.

A truly remarkable endeavour; An ex-pat Englishman shooting an American feature movie with almost no script, only two actors (the rest of the cast are real people being used as featured extras), no storyboard, a skeleton crew, shot entirely on location in a non-English speaking country. The result is a modern classic; ordinary boy meets ordinary girl amidst extraordinary times in unfamiliar landscape, laced with intrigue and danger, melancholy and ultimately a profound sense of tragedy, despite the thread of connection and possibility of love.

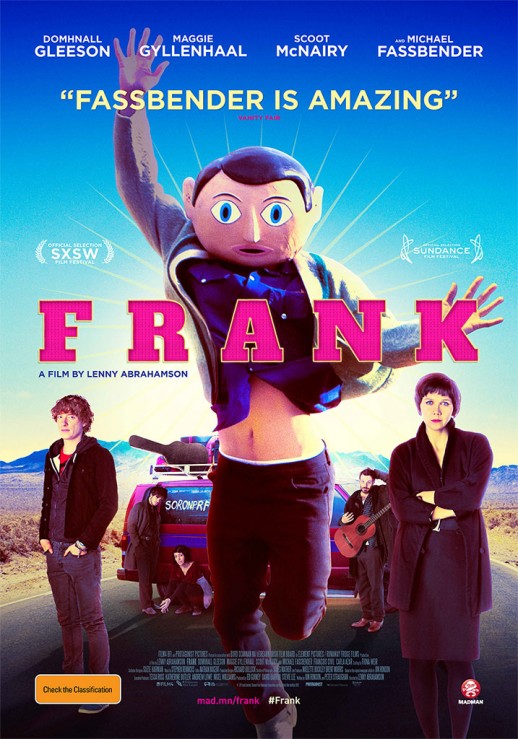

Scoot McNairy plays Andrew Kaulder, a twenty-something American photojournalist in Mexico, hoping for the scoop of his career thus far (capturing one of the monstrous alien creatures within the infected zone, or victims - especially dead children). He’s instructed to locate his boss’s daughter, Samantha (Whitney Able), who’s roughly the same age and on a vacation of sorts, and bring her safely back home across the US border. Kaulder isn’t too happy to be pulled from his potentially lucrative opportunity into a rescue mission. He finds Sam with an injured wrist in a local hospital, and they embark on the journey north.

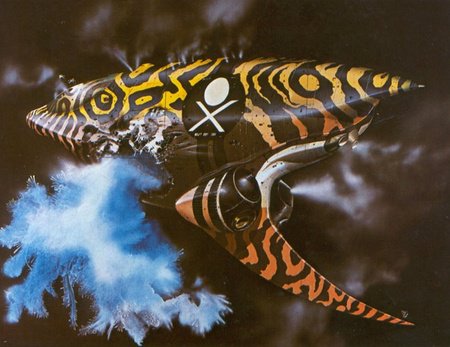

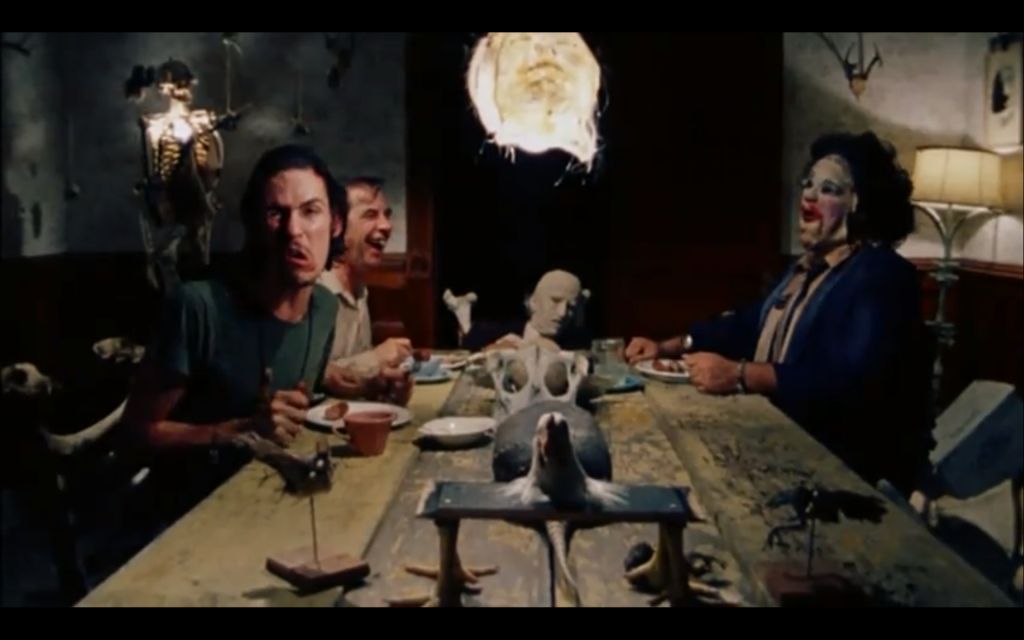

What begins as a road movie transforms into an elusive science fiction thriller, and ends abruptly as a romantic drama. But there is a deep sadness that permeates the narrative. This is instigated in a prologue sequence depicting the US military on a search and rescue mission, which culminates in an airstrike on one of the massive alien “octopus-spider” creatures, which involves Kaulder and Samantha as casualties. This isn’t immediately apparent, but can be confirmed upon repeat viewing.

Apart from the superb performances from McNairy and Able (and the great work elicited from the non-professionals), what makes Monsters such a powerful and intelligent movie is Gareth Edwards’ approach to tone and atmosphere. The narrative isn’t so interested in the bigger picture, although that is addressed, albeit ironically, even cryptically, by the movie’s title, but by the little moments within scenes, the nuances of the characters' expressions, through body language and reflection of thought. This is one of the most moving and unassuming love stories I’ve ever seen, exquisitely heightened by Jon Hopkins beautifully atmospheric, hugely emotive, ambient electronic score.

The vivid cinematography is often raw and urgent, and in places beautiful, even mesmerizing. Gareth Edwards not only camera-operated (on a consumer-level digital camera) and edited, but also designed all the CGI effects, including the amazing creature design, and the clever adjusting of existing signage, plus adding military vehicles, ruined buildings, etc. The dreamy mood and languid pace of the movie (although it's not a long film) may be uninteresting to viewers expecting a horror-action picture, but it is precisely this unusual hybrid of elements (especially for a Hollywood-looking movie, and I mean that in the best possible way) that makes Monsters such an affecting experience, both emotionally and psychologically. Not only my favourite movie of 2010, but it has secured a place as one of my very favourite movies of all-time.