2013 | US | Directed by Simon & Zeke Hawkins

Logline: A teen, his girlfriend, and buddy find themselves in a world of trouble after one of them steals from his boss and the other two become accessories.

You can say the Hawkins brothers’ debut feature is a poor man’s Blood Simple, but that would be doing it a disservice. Sure, this Texan neo-noir doesn’t play anything down we haven’t seen before, and it doesn’t play with the power of cinema narrative in the same magical way as Joel and Ethan Coen did with their debut feature, but what Simon and Zeke do is cement themselves as efficient and compelling storytellers, and, most importantly, more than capable of producing a film that captures the atmospheric essence of the genre.

B.J. (Logan Huffman), a brazen opportunist with an arrogant head to boot, steals twenty grand from his boss, Giff (Mark Pellegrino), whom he takes for an idiot. Unfortunately, B.J.’s buddy Bobby (Jeremy Allen White) spills the beans when Giff reveals his true colours as a sadistic thug. Next thing you know B.J., Bobby, and B.J.’s gal Sue (Mackenzie Davis), who shared in the reckless spending of Giff’s cash, have fallen foul of Giff’s master plan to get his moolah back.

Before you can say, “Finger lickin’, cotton’ pickin’, beer swillin’” Bobby’s getting his end in, B.J.’s eavesdroppin’, and Giff has the three teens caught up in the spokes of some dirty big time thievin’ from Giff’s boss Big Red (William Devane). But everyone has an ulterior agenda, including Sheriff Shep (Jon Gries), who spells out a sly warning to young Bobby.

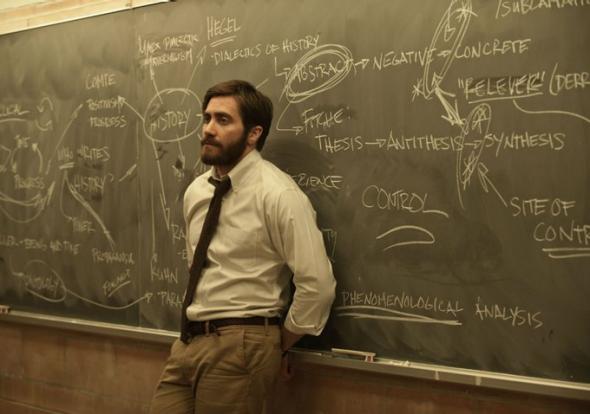

Penned by some dude by the name of Dutch Southern, yup, the movie’s original title (during its festival circuit) was We Gotta Get Outta This Place. Not the most inspired title, but essentially that is what B.J., Bobby, and Sue want, and what drives them. Sue and Bobby plan to go to university, whilst B.J. just wants to get the hell out of dodge. He doesn’t appreciate Sue’s literary passion, all those books with their fancy plots. Even Bobby finds Sue academic reach higher than he’s able to climb, but he’ll try and get a leg over if he can.

In one of the opening scenes Sue is in a café with Bobby discussing Jim Thompson, the legendary noir author. It’s a casual reference, which comes full circle at movie’s end. Later, in Sue’s bedroom, B.J. tries to seduce Sue, but ends up antagonising her, even threatening her in a passive aggressive way. If there’s a notable flaw with Bad Turn Worse, other than the second half not quite delivering on the danger and allure of the first half, it’s that the characters are almost too rich for the sauce they’re stewin’ in. And William Devane simply isn’t given enough screen time as the bathrobe-blazin’ big boss!

But hey, the lead performances, especially Huffman, Davis, and Pellegrino, are worth their weight in gold. Bad Turn Worse satisfies like a smoke after sex. Just don’t call it this noir a Cuban.