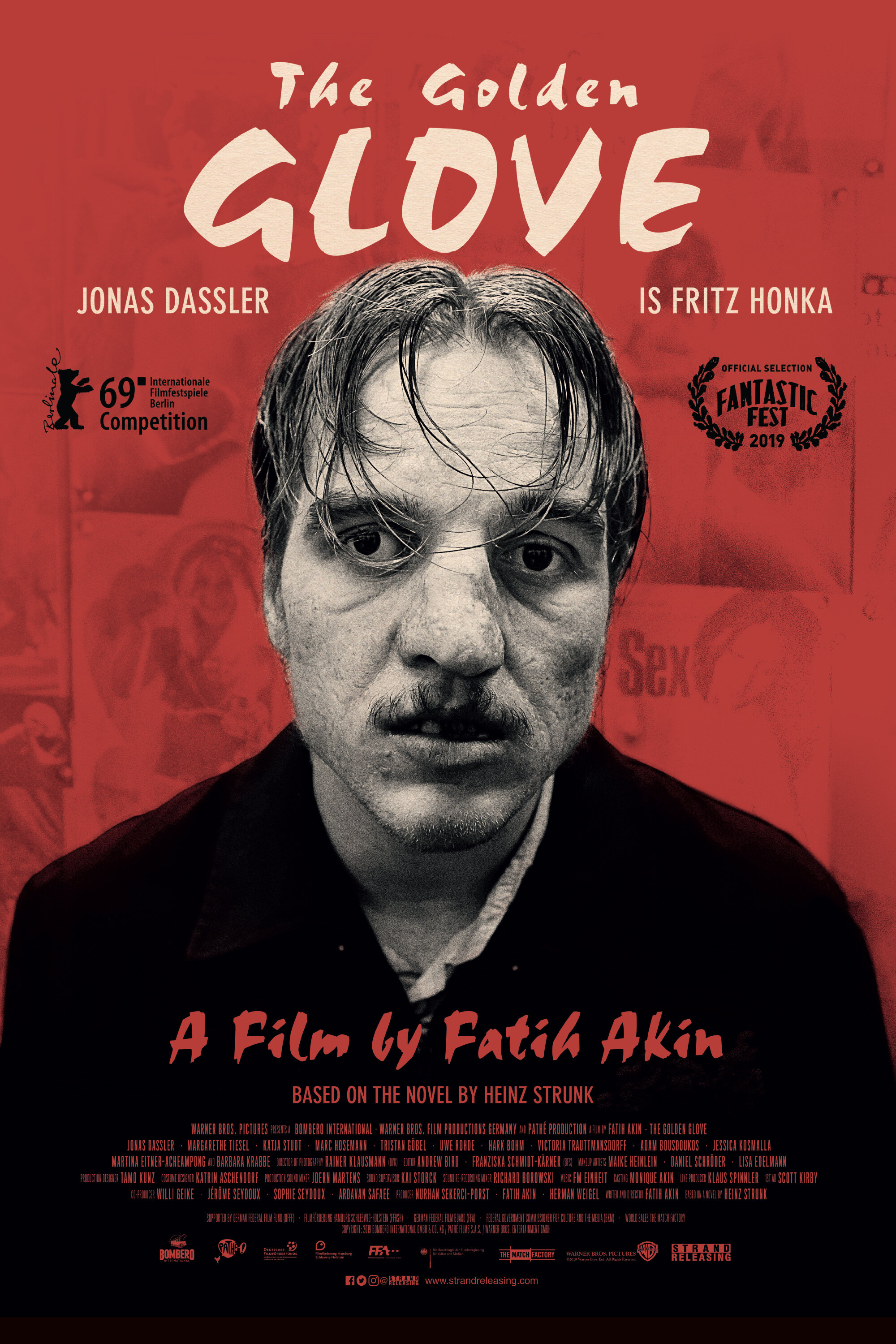

Der Goldene Handshuh | Germany/France | 2019 | Directed by Fatih Akin

Logline: During the mid-70s a German serial killer haunts a local bar and district, picking up destitute older women.

Akin is probably best known for the intense relationship drama Head-On from 2004. He’s made several features since then, but his latest is bringing him a whole new level of attention. It’s the kind of movie that can only be recommended to those with strong sensibilities. Relentlessly grim and grotesque, it’s so dedicated to the grime and squalor of its central character’s living and mental conditions that it seemingly transcends the trappings that would normally bury a study of such ghastliness.

The Golden Glove is based loosely on the book of the same name by Jeinz Strunk, which in turn is based on the true crimes of one Friedrich “Fritz” Honka, a lowlife barfly who brutally murdered several women during the 1970s, dismembering their bodies, but storing some of the parts within his cramped attic apartment in the seedy area of Hamburg’s red light district. It is at the local dive, Der Goldene Handshuh, where Fritz spends much of his time, surrounded by other drunks, most of whom have fallen out of the Ugly Tree and hit all the branches on the way down. Fritz is no exception, with his squashed boot of a nose, pockmarked skin, greasy hair, and bung eye, not to mention a pathetic shuffle. He drinks Schnapps like it’s going out of style, and fantasizies about a pretty frauline whose cigarette he lit as she looked the other way.

Fritz is a rapist and cold-blooded killer. He lures aging drunk women from the bar, back to his upstairs hovel, and after plying them with booze and bratwurst he tries to have sex with them, and then in frustration he bludgeons or strangles, or both. He’s a coward and a monster, yet his bar buddies are none the wiser. But the Greek family who live directly below are subjected to the horrendous smells emanating from Fritz’s lair, and Fritz tells the women he brings home that the rank stench is due to the Greeks’ cooking. It’s only a matter of time.

To call this movie seedy is being complimentary, to call this movie repugnant is by no means a disservice. It is both, and proud of it. But it is also exceptionally well made. It’s a stark portrait, no foul buts about it, a chipped and cracked mirror held up to the depths of depravity the human condition can sink to, a true reflection of darkness. The handsome looks of young actor Jonas Dassler have been completely removed to portray Honka, and his committed performance is one of the standouts of the year, if you can handle it. But, it’s not just Dassler, the entire cast are uniformly excellent.

The production design, art direction, and costuming are all bang on; the mid-70s’ back streets of Hamburg have been meticulously recreated, decorated, and retro-fitted. It’s impossible to fault the movie in any department. This is a true crime horror movie dressed as a period piece character study. It’s as sordid, nasty and hideous as Mike Leigh’s Naked, and also just as provocative, fascinating and truthful.

“Life's a card game. If you want to pIay, you have to take the hand you're dealt.”