US/Germany | 2013 | Directed by Matt Wolf

Logline: A documentary that traces the “creation” and progression of the teenager from the end of the 19th Century through to the middle of the 20th Century.

Based on the book Teenage: The Creation of Youth Culture 1875 – 1945 by Jon Savage, who is given co-writer credit along with the director, Teenage is a fabulous and refreshing overview of the so-called rise of the adolescent creature that now dominates the modern para-social world we currently live in. It is fascinating, endearing, provocative, and, at times, heartbreaking. But ultimately, it is uplifting.

Before the end of the 19th Century people were classed either young or old. The period of adolescence from the age of 13 to 19 was a grey area that existed, but was never indulged, and certainly not enjoyed by its kind. The pressures of living and working during every historical age culminating with the industrial revolution dampened any kind of joy of being young and curious.

But slowly and surely the voice of the young adult began to emerge. Through the flappers and the bright young things, the youth movement stirred and clambered, it shimmied and swang, tearing apart a divide between children and adults. A new generation was born, and it liked to have fun.

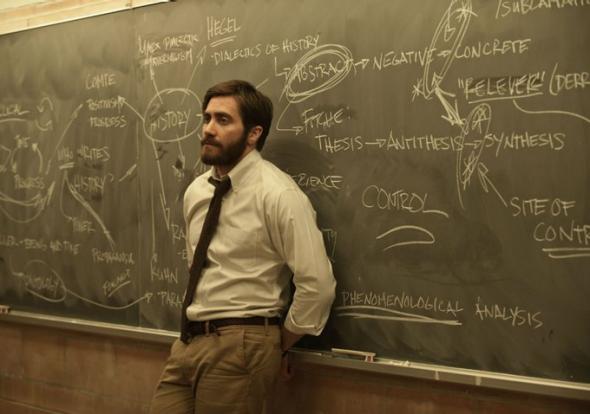

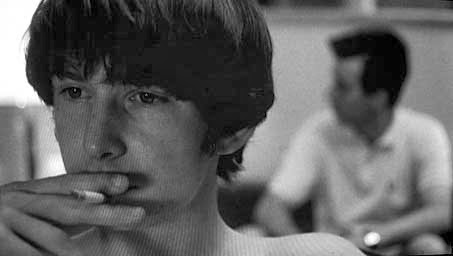

Matt Wolf’s fabulous documentary is a celebration of fantastic never-before-seen archival clips and still photos dating back to the very early part of the 20th Century. Using this collage of, mostly, black and white imagery, Wolf then adds his own filmed portraits of American, English, and German teenage abandon across the decades, each shot in the respective period aesthetic. On top of this he uses actors, including the distinctive voices of Jena Malone and Ben Wishaw, to narrate from diary entries.

War and music are the two most powerful elements that shaped the hood of the teenager, especially the two World Wars and Swing music. Jitterbugs and Sub-Debs became the voice of youth, the sound of freedom, despite the restrictive attempts by Hitler (who deemed that swing music was only fit for niggers and jews) and other rule-abiding stick-in-the-muds out to destroy their carefree spirit.

Eventually by the end of 1940s the teenager was being championed with publications such as Seventeen. A new socio-political history had been established. The teen-ager had become teenager. They were going somewhere. Rock and Roll was just around the corner.

What gives this documentary a particularly memorable edge is the contemporary score by Bradford Cox, ambient-flavoured musings, similar in melody and tone to Fila Brazilia and Boards Of Canada. The music offsets the vintage imagery and gives it an utterly fresh context, a surge of melancholy floods the perspective, yet provides an unusual vitality.

This is one of my favourite films of the year.

Teenage screens as part of the 8th Sydney Underground Film Festival, Saturday 6th, noon, and Sunday 7th, 1pm, at Factory Theatre, Marrickville.