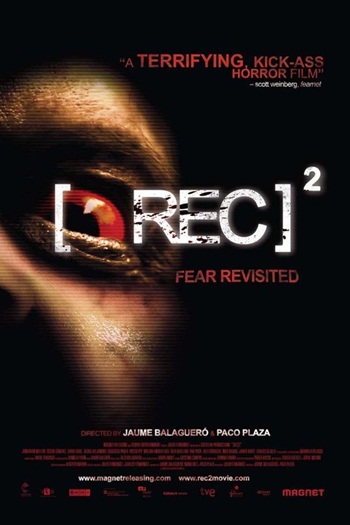

Spain | 2007/2009 | Directed by Jaume Balagueró & Paco Plaza

Logline: A reporter, numerous firemen and tactical police, a doctor, and local residents, are quarantined within an apartment block that has been infected with a diabolical virus.

Plucky young television presenter Angela Vidal (Manuela Velasco) and her cameraman Pablo (he’s never seen and no one is credited to playing the character) are doing a piece on the night-shift at a Barcelona fire station for the programme “While You’re Asleep” and hoping for a little emergency action to spice things up.

Sure enough, in the wee hours they’re off to rescue an old woman trapped in her apartment. When they get to the building police are already there. Inside the woman’s apartment they discover she’s covered in blood, deranged and dangerous. In fact, she’s in a raging, ravenous fit, and she chomps down on the neck of one of the police officers.

Everyone retreats, but not before one of the firemen gets bitten also. It soon becomes apparent they have been infected with something. Before anyone can be evacuated the entire building is sealed off and quarantined. For the remainder of the movie Angela and the surviving others must navigate the building, floor by floor, trying desperately not to be bitten by the infected.

The tension and suspense is ratcheted right up after Angela and Pablo break into the penthouse apartment, which had supposedly been abandoned by the owner. Inside they find the walls plastered with revelatory newspaper clippings. It seems they’ve stumbled onto a can of real nasty worms.

The Blair Witch Project put the found footage sub-genre back on the map, but it was another eight years before the format really took off, and [REC] was the movie to do it. Plot mechanics pared back so vehemently one wonders if the original treatment ran longer than a paragraph. Balagueró and Plaza tapped into a throbbing jugular, pulsing with the tainted blood of the good old-fashioned things-that-g0-bump-in-the-night and the viral volatility of 28 Days Later, harnessed in real time.

[REC] kicks serious butt, especially the second half. Manuela Velasco holds fort like a champion, the support cast are solid, and what an ending!

But it ain’t over ‘til the thin lady screams. [REC] 2 continues the rabid urban nightmare as members of the GEO (a Police Tactical Unit) team accompany a medical expert, Dr. Owen (Jonathon Mellor), into the quarantined apartment building in a vain effort to get a blood sample from the young girl, Medeiros, who was the very first infected. The doctor believes an antidote can be created. But first they must find her.

To complicate matters, three mischievous teenagers; Ori (Alex Batlloir), Tito (Pau Poch), and a hesitant girl, Mire (Andrea Ros) decide to follow a fireman and a distraught husband/father down a manhole and up inside the infected building. The manhole is welded shut.

I like to call the sequel [REC] Part 2 as chronologically it carries on directlyfrom the first movie (like Hostel: Part II and with that in mind Halloween II should’ve been Halloween Part II, but I digress...) [REC] 2 is the easily one of the best horror sequels. Two years after the first movie Balagueró and Plazareturn with a vengeance, maintaining the same intense level of chaos and hysteria, but upping the ante, and twisting the supernatural origins with a heinous screw, culminating in a brilliant denouement (forget the third and fourth installments in the series, it starts and ends here).

There’s not an awful lot of plot going on, it’s about the immediacy of the situation and the overall visceral experience, as seen and heard through the video recording taken by TV cameraman Rosso (now identified as cinematographer Pablo Rosso), in the first movie, and by several of the GEO team (Rosso again as a different character, but obviously returning as cinematographer) who have camcorders mounted on their helmets, in the sequel.

Like the best found footage flicks there is a genuine sense of urgency and palpable dread that exudes through the shaky-cam, the editing, and the excellent use of the location shooting. The infected humans in the [REC] movies are like the Rage-infected from 28 Days/Weeks Later, they move fast and furious! I love my shuffling undead, but the menace factor in the [REC] movies is ferocity to be reckoned with.

The brilliant plot device of the first movie is returned to when the GEO team use their helmet cam’s night-vision during the movie’s last ten or so minutes, after Dr. Owen and a few others have returned to the penthouse apartment. It is exclusively Dr. Owen’s voice command to the outside that will allow the surviving team’s rescue.

But there’s hell to pay. And suffice to say that all hell breaks loose.

An atmospheric authenticity is crucial to both [REC] movies, suffice to say, the sequel even tops the first movie with its attention to detail. Perhaps not quite as confronting with the initial premise, simply because we’re returning to the scene of the crime (or is that accident?), but certainly the violence is ramped up, performances are strong, the creep factor enhanced, and all the panic buttons are pushed at once.

[REC] & [REC] 2 are lean, mean, killing machines, short, brutal, brilliant, and with no score. I insist that they be watched back-to-back. With birra at hand.

![[REC 2] Parte 3 HD.mp48.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/50d144f6e4b05aff8e5b9c8c/1539732263485-HR3D2FOLAF7U0IOMUU2H/%5BREC+2%5D+Parte+3+HD.mp48.jpg)