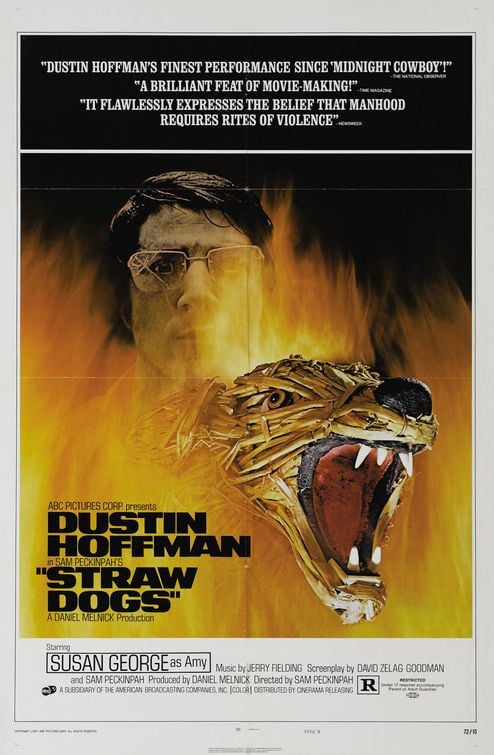

US/UK | 1971 | Directed by Sam Peckinpah

Logline: An earnest American and his young English wife settle in rural England and face increasingly vicious local harrassment.

At surface level a powerful study of violence both implicit and explicit, but under the skin, Straw Dogs is a complex and disturbing morality play that poses far more questions than answers. It provokes and outrages, yet by the end offers only slight reward, leaving a bitter taste of copper, and the acid after burn of contempt. After the assault on the senses that is the siege at Trencher’s farm, empathy is left in ruin, humanity torn a sunder.

Two years prior Sam Peckinpah had delivered one of the great, uncompromising Westerns, The Wild Bunch (1969); a ruthless, indulgent portrait on male self-righteousness, bravado and violent machismo. It was a farrago of raw energy and moral corruption. Peckinpah then polarised audiences even further, pushing his dark fascination with the human spirit and society’s innate misanthropy to a deeper, more insular level. Straw Dogs would tear apart all notions of love and trust, of jealousy and desire, and of man’s acumen for violence.

Based on the novel The Siege of Trencher’s Farm by Gordon Williams and adapted for the screen by David Zulag Goodman and Peckinpah, Straw Dogs tells the story of meek and mild David Sumner (Dustin Hoffman), an American mathematician who, with his pretty young wife Amy (Susan George), has moved from the States back to Amy’s home of Wakely, a small village on the coast of England, where she grew up. They’ve bought an old farmhouse up on the hillside that needs repairing, so David has hired a few of the local handymen, so that he can concentrate on his treatise on celestial navigation (the “astro-mathematic structures of stellar interiors”).

One of the builders is Charlie (Del Henney); an ex-lover of Amy’s who makes it very obvious he still carries a torch for her. Amy is flattered by his attention, but won’t stand for his sleazy behaviour. Charlie and his cohorts, Norman (Ken Hutchison) and Chris (Jim Norton) despise David, and challenge him by inferring he’s a milquetoast for abandoning his country in time of need (the Vietnam war). There’s tension between David and Amy as well, since David is so wrapped up in his equations and seems only to patronise Amy, leaving little time for genuine loving. Amy is restless, David is preoccupied. Frustration and neglect will soon collide, and tragedy will ensue.

Straw Dogs is such a thematically rich and intelligent work, darkly provocative, nightmarish, subversive. The characters don’t fit any easy mold, all drifting within a morally grey area. Obviously there are some that can be easily pigeon-holed as villainous, but there are agendas exposed that suggest not all intentions were evil at heart. If only ...

The most controversial part of the movie is the rape scene (which got the movie into a lot of trouble when it was first released and in the years following), or more precisely Amy’s response to Charlie’s rough attempt at seduction. It is apparent Amy still harbours an attraction toward him, but he’s by no means the man who makes her laugh, as her husband does. Amy’s flaunting of her naked body, and not wearing a bra beneath her sweaters, has been driving Charlie wild with lust.

WARNING! CONTAINS SPOILERS!

After orchestrating a snipe hunt for David, where the men stick it to him in the bush, leaving him floundering on the hilltop waiting for pheasants and ducks to fly by, Charlie arrives back at the farmhouse and surprises Amy who invites him in for a drink. But it’s more than booze Charlie’s after. He forces himself on Amy, she slaps him, he pulls her by the hair over the sofa where he pins her down and tears her robe and panties off.

At this point the assault changes gear. It appears no longer to be rape, but consensual sex as they have intercourse and she caresses his face and they kiss. It began as forced entry, but has become something far more complex. The image of Charlie is intercut with David, both men making love to her. But is Charlie providing a more passionate experience for Amy? “Hold me,” Amy whispers. Suddenly Norman is there in the room also, brandishing a shotgun. Amy isn’t aware as she lies on her stomach, her eyes closed in a state of post-coital satiation. Whilst Charlie holds Amy down, Norman sheds his pants and sodomises her. Amy screams in shock and pain. The first intercourse had been questionable in its reception; the second is violation, impure and simple.

David never finds out about the rape, which makes his act of defiance in the last third of the movie a curious stand. One would expect the drama to come from David seeking revenge, but Straw Dogs confounds this by having David respond to something more prosaic: one man’s house is his castle and should be protected at all costs. It is here that David’s failings as a husband and his strengths as a coward in turnaround are made explicit. He was witness to Charlie’s blatant interest in his wife, and he was too cowardly to confront the men about the killing of Amy’s pet cat, yet when David has brought the local pederast, Henry Niles (David Warner, in an uncredited role), into his home after accidentally hitting him with his car and the village lynch mob have come to collect him because local girl Janice (Sally Thomsett) is missing, presumed dead at the hands of Niles, David refuses to give him over. It is here where the siege takes place, and where David turns the tables on his attackers.

Whilst Amy is hysterical, David is transforming, becoming less human, more animal; less logical, more instinctual. But the most telling and the most distressing point is not made until the very end. Having dispatched all of the assailants in numerous violent ways, David tells Amy to stay in the house while he drives Henry Niles down to the village, even though he can’t be sure all the attackers are dead. As they drive through the impenetrable darkness Niles says, “I don’t know my way home.” “That’s okay,” David replies with a strange smirk, “I don’t know either …”

Straw Dogs deals with game-playing and the strategy of battle as metaphors and symbolism. We see Amy playing chess in bed, David working on his elaborate mathematical equations on his huge chalkboard, David and Amy fool around as if on a perpetual one-on-one game of their own making, David taunting the cat by throwing fruit at it, there’s the snipe hunt David is coerced into going on, and of course, the final siege, which is a series of confrontations and dispatches. There’s also the strange voyeurism that involves Janice and her brother Bobby (Len Jones), spying on David and Amy. Janice has a crush on David, but she ends up manipulating Henry Niles, as if on some strange death wish.

There’s also a thematic element concerning immaturity and its potent fragility in relationship to experience and innocence. “You act like you’re 14,” teases David to Amy, “I am!” she replies with a cheeky laugh. Charlie, Norman and Chris all act like they’re adolescents, bragging and cajoling each other. Henry Niles is a man-child. And of course David and Amy are cocooned in a bubble of immaturity as well.

Peckinpah’s direction is superb, helped by atmospheric cinematography from British cameraman John Coquillon. The editing is brilliant, especially the inter-cutting during the church social gathering which highlights Amy’s paranoia and trauma, and also during the siege (three editors, plus an editorial consultant were employed on the movie). The score, mostly sombre brass and woodwind, captures a suitably terse mood.

The performances are all first rate. Hoffman is at the top of his game (and only a couple of features into his career) playing the emotionally retarded stranger in a strange land, while Susan George matches him with her delicate balance of vulnerability and assertiveness. The support cast can’t be singled out, they’re all great.

Straw Dogs is a difficult movie; but for all the best reasons. It presents the moral quagmire of human frailty, it slaps you in the face, slashes you, and leaves you scarred, with blood on your hands.

“Heaven and earth are not humane, and regard the people as straw dogs.”