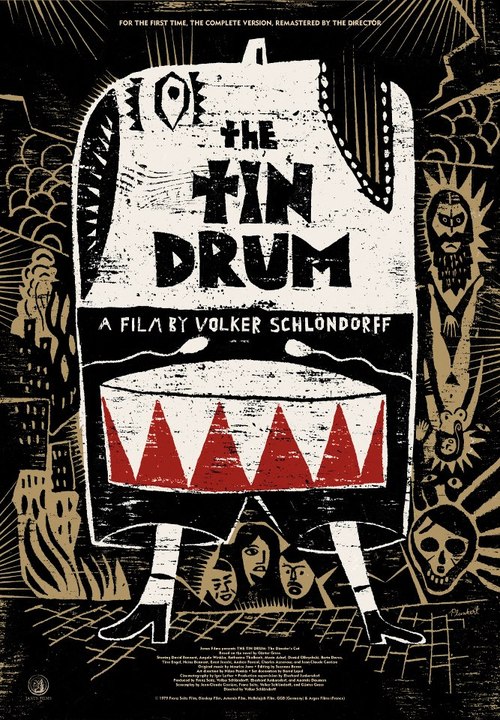

Die Blechtrommel | West Germany/France/Poland/Yugoslavia | 1979 | Directed by Volker Schlöndorff

Logline: In Danzig, Germany, as WWII begins, a three year old boy with extraordinary intellect and a distorted morality decides to stop growing in defiance against the absurdity and contradiction of the adult world he sees around him.

Based on the 1959 best-selling novel by Günter Grass Die Blechtrommel is a saga of morality, deception and resignation. It is a tale that resonates with dark poignancy, reverberates with an element of the perverse, and echoes with touches of surrealism. It’s a film of disquieting brilliance that won the Palm d’Or at Cannes and the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

Central to the film’s conceit is the extraordinary performance of young David Bennent who was 12-years-old, but plays troubled Oskar from an infant through to almost 21. His odd features, like that of an old man trapped in a child’s body, captures perfectly the sense of curiosity and exasperation that is Oskar. He is both inquisitive, yet defiant in his perspective of the world.

Adults are creatures of lies and betrayal, and foolish folly gives way to ignorance and tragedy. As Oskar realises the followers of Hitler and the Nazi party have mistaken him for Santa Claus, but really he was the Gas Man. World War II becomes both a literal and figurative metaphor for the lust and corruption that permeates Oskar’s world. His family is torn apart, as his German father Alfred (Mario Adorf) is seduced by the Fuhrer and his Polish uncle Jan (Daniel Olbrychski) is ostracized. His mother Agnes (Angela Winkler) is sleeping with them both, and Oskar finds himself inexorably instrumental to their plight.

Right from the dreamlike opening scene where Oskar narrates how his grandmother met his grandfather and conceived his mother in a potato field, the tone and style of the film is set; Fellini-esque, yet with strong Eastern-European flavours. The rustic, striking cinematography enhances the vivid visual narrative, while Maurice Jarre’s distinct score adds an unusual sense of black humour to the drama.

The film constantly contrasts images of beauty and sensuality against the grotesque and disgusting; a decomposing horse’s head is pulled ashore with eels snaking in and out of its orifices, Oskar is forced to drink frog and urine soup. Oskar climbs to the top of a bell tower with his trusty tin drum, surveying the spectacular view, then hammering away and screeching his glass-shattering vocals. Oskar’s tin drum is omnipresent, and when it’s damaged, he gets a new one. Apart from his unusual voice, the tin drum speaks for him. It challenges everything he doesn’t like or understand.

The film has courted controversy for its depiction of Oskar’s sexual awakening, in particular two scenes with his father’s young lover Maria (Katharina Thalbach): Oskar (aged 16, but still looking like he’s barely 10) buries his face in Maria’s naked crotch, and he shares her bed, licking sherbert from her navel, then mounting her. These are important moments, integral to the story, and are filmed tastefully, but the film was banned in the State of Oklahoma for many years, and was cut in the UK for breaching the law for the Protection of Children Act. The film has since been recognized for its artistic merits and the ban and the cuts have been waivered.

Die Blechtrommel is an utterly unique film, often startling, frequently amusing, strangely sensual, curiously affecting. It’s a beautiful and sad parable – and a savage satire – of prevailing innocence, corruption and inhumanity, hope and acceptance … and the simple chaste beauty of the potato.