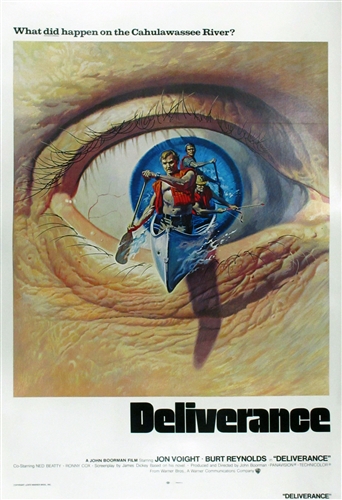

US | 1972 | Directed by John Boorman

Logline: Four adult friends embark on a weekend canoe trip only to be terrorised by angered backcountry woodsmen.

Based on the brilliant first novel from James Dickey, an acclaimed American poet and university lecturer, who also wrote the excellent screenplay, Deliverance is a deeply impressive, but harrowing portrayal of masculinity, and the ferocious nature of man, that has lost none of its visceral power since it was first unleashed back in 1972. It is a tale of shattered innocence and ruptured, primal machismo, with an undercurrent of social and eco commentary (awe and contempt) that is apparent only through the movie’s superb use of symbolism and metaphor. Freedom is sought with single-mindedness, but the darkness of the soul is eventually laid bare, only after the mind and body is subjected to humiliation and violation.

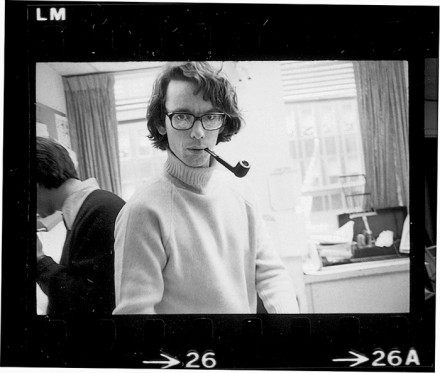

Lewis (Burt Reynolds in a breakthrough career performance) is the macho leader, an imposing go-getter, who loves the great outdoors. Accompanying him are his buddy Ed (Jon Voight), a pipe-smokin’ family man who likes a tipple and a challenge, Drew (Ronny Cox), another family man, with strong morals and a dab hand on the guitar, and chubby Bobby (Ned Beatty), who likes to complain, but yearns to cut loose. These four friends drive up into the heavily-wooded Appalachian hills and negotiate for some local moonshiners to drive their two cars down the mountain road trail to the Aintry river-stop where they’ll rendezvous in their canoes a couple of days later. The greasy feral mountain men wonder what the hell they wanna tackle the river for. “Cos it’s there,” replies Lewis smugly.

Not a scene or shot is superfluous in Deliverance. I raise my hat to the consummate skill of Boorman and Dickey, who along with late, great cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond (one of my favourite DOPs), editor Tom Priestley, and special effects technician Marcel Vercoutere, fashioned a nightmare thriller as sharp and deadly as the powerful bow and arrow brandished by Lewis and Ed (which is almost a character in itself, the other “character” being the Chatooga River – renamed the Cahulawassee in the movie - which divides South Carolina and Georgia).

The performances from the four leads are terrific, especially Jon Voight. It was Ned Beatty’s first movie, but special mention must go to Bill McKinney as Don Job, who forces poor Bobby to squeal like a pig, a nasty piece of work he is, and with few lines to utter, Herbert ‘Cowboy’ Coward, as Job’s toothless grinnin’ bosom buddy. These two backwoods bandits are an understatedly fearsome pair (decades later McKinney named his own website squeallikeapig.com!)

It’s hard to believe but the Deliverance production was uninsured. The actors all performed their own stunts, the rapids tossing resulted in Burt Reynolds breaking his coccyx. Jon Voight actually scaled the sheer vertical cliff face. Ned Beatty was the only one who had any canoeing experience, the others learnt on location. To further minimise costs, locals were hired to play the resident hillbilly folk, with one elderly gentleman improvising a buck jig which was included in the movie.

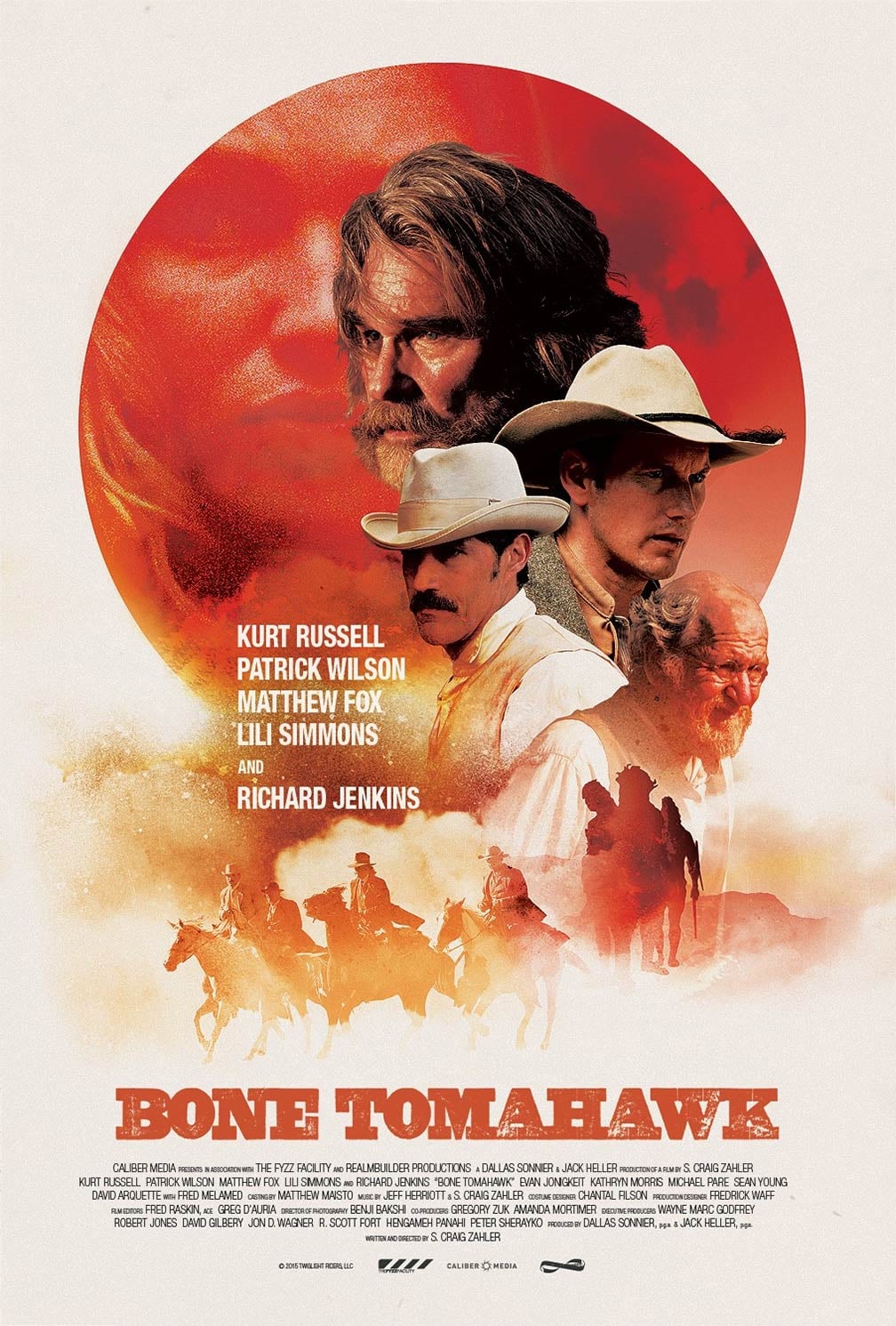

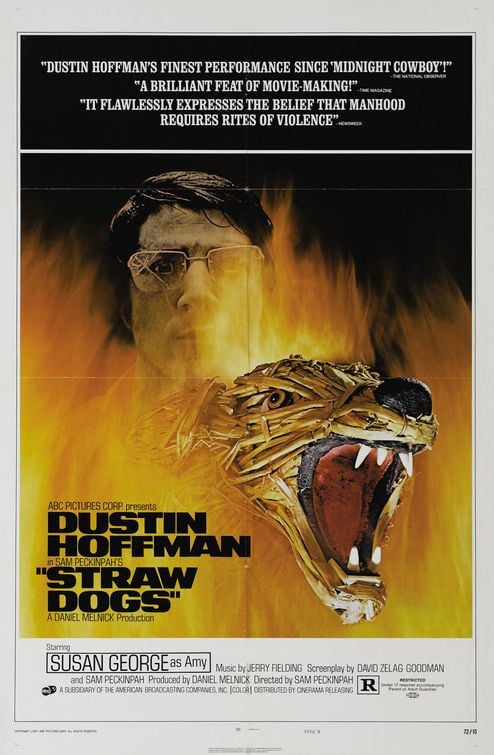

Sam Peckinpah wanted to direct, and when Boorman was signed on Peckinpah went off to make Straw Dogs. Donald Sutherland turned down one of the roles because he objected to the violence (and later regretted his decision), yet ironically a year later he starred in Don’t Look Now (1973). Charlton Heston and Marlon Brando both declined the role of Lewis, as did Lee Marvin for the role of Ed, telling Boorman he thought he and Brando were too old for the parts. James Dickey appears in a small, but convincing, part as the Aintry Sheriff who suspects the men’s story might be a little taller than they’re admitting to.

There’s an apocalyptic atmosphere that permeates the narrative of Deliverance, the title of which is a clever play on being rescued or set free and a thought or judgment, often from an authoritative voice. In this case, the title suggests the pursuit of unbridled adventure amidst the wilderness that is being threatened by urban development (the damming of the river) and the plunder of human progress. Dickey was passionate about this socio-political stance and he designed his novel as a nightmare metaphor. Boorman had a kinship with Dickey and used his skill as a director to design a mise-en-scene, a vivid, succinct visual narrative that employed both symbolism (Ed’s faltering when he tries to kill a deer and the river reducing Lewis from He-man to whimpering invalid) to the analogy of the violence of man’s inhumanity to man vs. the violence of humankind’s geographical greed.

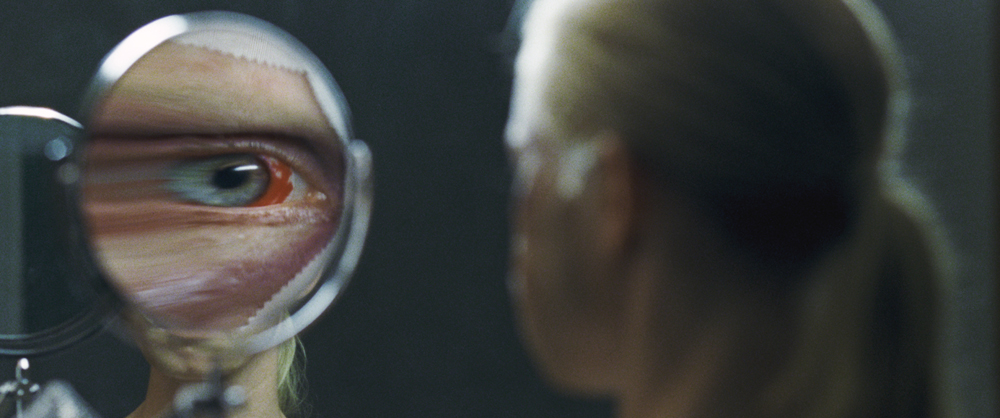

Whilst nowhere near as graphically violent as most of today’s R-rated horror movies, Deliverance still contains the power to shock and upset, especially in the infamous rape and murder sequence, and later when we witness Lewis’s horrendous leg injury (that’s one gruesome compound fracture!), Ed impaling himself on an arrow, and the discovery of Drew’s twisted corpse (Ronny Cox suggested taking advantage of having a double-jointed shoulder!). There is an implicit violence that courses through the entire movie, despite the natural beauty of the surroundings. The movie even ends in a dream-like paroxysm of guilt and fear … and finally stillness, but with anxiety floating just below the surface.

The only thing that dates Deliverance is the use of day-for-night shooting during Ed’s nocturnal scaling of the cliff. In 1972 anamorphic lenses and film stock were a lot slower and night scenes had to be under-exposed and given a blue tint during post-production. Little else apart from that gives Deliverance away from being nearly forty-five years old (it’s not like mobile phones would’ve helped the men’s predicament!) Even the famous “Duelling Banjos” scene somehow seems ageless.

In Germany the title was changed to (and translated as) In Dying, Everyone is First.