UK/France | 1997 | Directed by Gary Oldman

Logline: A working class family, and their immediate friends, struggle to deal with alcoholism, drug addiction, and domestic violence.

“I remembered that day ... because I could've put that on his fucking tombstone, you know? Because I don't remember one kiss, you know, one cuddle. Nothing. I mean, plenty went down, not a lot come out. You know, nothing that was any fucking good ... He was fucking freezing cold. It frightened the life out of me. I was looking at him, you know? For the first time in my life, I talked to him. I said, ‘Why didn't you ever love me?’”

Based on his own experiences growing up Gary Oldman penned an utterly uncompromising, searing portrait of addiction and violence. With French director Luc Besson an unlikely co-producer it is the grim as nails life and times of South-East Londoner Raymond (Ray Winstone), his pregnant wife Val (Kathy Burke), her young brother Billy (Charlie Miles-Creed), and their immediate friends and family, a devastating, blistering nightmare of working class urban disease.

Billy is an adolescent, a junkie, and a thief. He does petty crime for Ray and his mate Mark (Jamie Foreman, son of the notorious Cockney gangster Freddie Foreman), and steals Ray’s stash. Ray is a violent, belligerent thug and an addict too, and doesn’t think twice in viciously assaulting Billy when he confronts him over the theft. They are a family trapped in a vicious circle of drug and alcohold abuse and domestic violence. But the worst is yet to be unleashed.

Val and Billy’s mother Janet (Laila Morse, Oldman’s sister) spends much of her time socialising with them, and their grandmother Kath (Edna Doré) is often included in get-togethers, as is Michelle (Leah Fitzgerald), Ray and Val’s young daughter. Billy hangs out with his heavily tattooed mate Danny (Steve Sweeney). Val hangs out with her girlfriend Paula (Chrissie Cotteril) and her partner Angus (Jon Morrison). They all spend much of their time at the local pub or in front of the telly at home getting blitzed, but no one more so than Ray, while Billy’s smack habit is getting out of control.

Shot with mostly handheld camera, using available light, filling the background with non-professional actors and locals as extras, and employing the thick Cockney vernacular, Nil by Mouth has an authenticity and gritty realism like a fly-on-the-wall documentary. This is enhanced ten-fold by the extraordinarily convincing acting of the core cast, of which Ray Winstone’s central performance is monumental in its ferocity and conviction (his inebriated monologue to his own reflection is something to behold). How he could not have been nominated for an Academy Award is a travesty (just as David Thewlis’s snub was for Naked). Mind you Kathy Burke is particularly affecting (and upsetting as her character drinks and smokes whilst pregnant), and she won Best Actress at Cannes for her role as Valerie.

I have never seen such a frightening drunkard on film as the Raymond of Nil by Mouth. The movie is dedicated to the memory of Oldman’s father, so is it safe to assume that Raymond is modeled on Gary’s own dad? If so, Nil by Mouth is a desperately sad obituary, depicting the harshest of truths that most violence is part of a cycle of poverty and bad parenting. It might sound like a terribly clichéd analogy, but love makes the world go round, without it the cogs seize, the giant machine crashes, and blood is spilled.

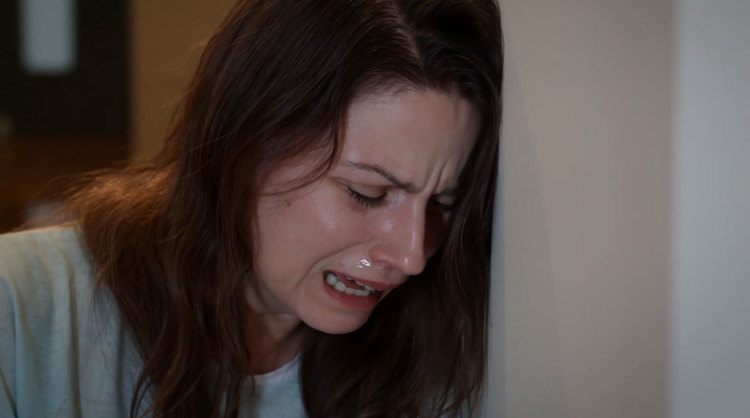

What is most horrendous is not Billy’s junk habit, not any of the appalling verbal abuse hurled from the mouths of Billy to his mother, or from Ray to Billy or Val. There is a scene of physical violence when Ray assaults Val and beats the living daylights out of her borne of his own drunken jealousy and coke-addled paranoia. The beating is terrible to witness (although it’s actually delivered out of shot from the camera), but when we see the horrific nature of Val’s injuries and her denial to her mother that it was Ray who beat her, the effect is absolutely devastating. This is the kind of violence too close to home, the kind that riddles broken families, the kind that is so often never reported.

Special note must go to the awesome special effects make-up applied to Kathy Burke (although how her wounds heal faster than the “love bite” on Billy’s nose is a small distraction), and to the use of music; Eric Clapton provides a surprisingly low-key score, while additional songs are used to punctuate scenes, including two evocative nu-soul tracks from singer Frances Ashman.

As repellent and harrowing as this domestic scenario and its surrounding seedy London working class is, Gary Oldman has made a darkly brilliant and dangerously compelling movie (his one and only as director). The last scene echoes on a disquieting note; the extended family gathered around discussing the plight of incarcerated young Billy who has narrowly escaped death. They joke about him being moved to the infirmary wing housing the freaks where he’ll probably get raped. The family is re-forming a dysfunctional bond, over the violent misfortune of one of their own. Very little has changed. This is no morality tale, yet Nil by Mouth paints a hellish picture that speaks a thousand hardened words.

“When you go out, you go with your mates ... and when you are in, you're pissed asleep in front of the television. I'll turn the television off, go to bed ... you follow me at three in the morning stinking of booze. That's what I get. Either that or you're knocking me about. I'm 32 today, you know, and I feel so fucking old. You know, I'm so tired. I wanna be able to look back and say, "I had a bit of fun." Instead of saying, ‘Everyone fucking felt sorry for me.’ I mean, that's the life I've got. Do you hear what I'm saying? I just don't want it. I'll find somebody else. You know, someone who can love me. Someone kind.”