US | 1979 | Directed by Francis Ford Coppola

Logline: During the Vietnam War a US captain is forced into one final mission; to locate and terminate the command of a rogue and delusional US colonel.

“I turned to the wilderness … And for a moment it seemed to me as if I was buried in a vast grave full of unspeakable secrets. I felt an intolerable weight oppressing my breast, the smell of the damp earth, the unseen presence of victorious corruption, the darkness of an impenetrable night.”

There are very few nightmare movies as visually, viscerally and psychologically affecting, as profoundly immediate, despite their historical settings, as Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. There has been so much said and done, so much dirty, bloodied water under the war-torn bridge of this extraordinary production, that any humble review in the wake of its questionable destruction, its primal majesty, its philosophical musings is purely grist to the mill. But a few more words scattered to the critical winds won’t hurt. This is a movie that has remained in my heart of dark delights ever since I first saw it cropped on a dodgy rented VHS with its original end credits rolling over a montage of the Kurtz compound being destroyed by what appeared to be an air-strike. It is one of my three favourite movies of all time; it is a war movie to be experienced like a “bad” acid trip, infused with dangerous awe and nightmarish wonder.

“Everyone gets everything he wants. I wanted a mission, and for my sins, they gave me one. Brought it up to me like room service. It was a real choice mission, and when it was over, I never wanted another.”

It is 1969. Captain Willard (Martin Sheen in a career performance) is a Vietnam veteran on the edge, well-seasoned, overcooked, but craving, is plucked from his squalid hotel room in Saigon and given an important intelligence briefing by Colonels Corman (G.D. Spradlin) and Lucas (Harrison Ford): “To proceed up the Nung River in a Navy patrol boat. Pick up Colonel Kurtz's path at Nu Mung Ba, follow it and learn what you can along the way. When you find the Colonel, infiltrate his team by whatever means available and terminate the Colonel's command … Terminate with extreme prejudice.”

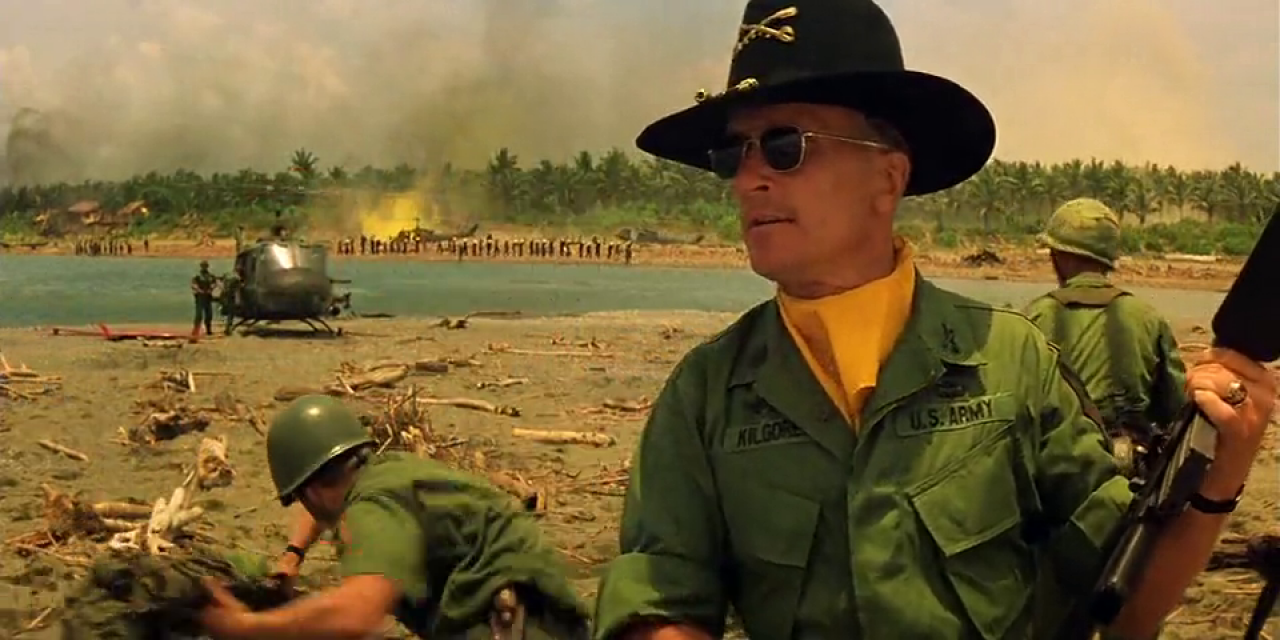

On board the PBR (patrol boat, riverine) is his “streetgang”; Navy Chief Phillips (Albert Hall), Californian surfer Lance (Sam Bottoms), Bronx boy “Clean” (Laurence Fishburne, just 14 years old when filming started), and New Orleans machinist “Chef” (Frederic Forrest). Willard notes they’re “mostly kids; rock and rollers with one foot in their grave.” After a bizarre excursion accompanying Lt-Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall, terrifyingly impressive) and his air cavalry on a “Ride of the Valkyries” - “Someday this war's gonna end ...” – Willard and his crew begin in earnest their deadly mission up the Nung River into the heart of darkness …

“I watched a snail crawl along the edge of a straight razor. That's my dream; that's my nightmare. Crawling, slithering, along the edge of a straight razor ... and surviving.”

Apocalypse Now is less a conventional narrative arc, and more a series of incidents and set-pieces building toward a final metaphorical assassination. It is war as allegory, movie as experience, nightmare as expressionist deliverance. Wholly inspired by Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness, a perilous journey into a quagmire of humanity, and based on an original screenplay by John Milius titled The Psychedelic Soldier, director Coppola pared everything back and then laid on the audio-visual schematics with a spade. Michael Herr was brought in to write Willard’s excellent narration. His intention was to create a spectacular adventure rich in theme and the philosophic inquiry into the mythology of war. The end result was a strange and demanding experience ahead of its time, yet distinctly of its time.

Apocalypse Now was one of the last masterpieces of arguably the greatest decade in the history of film. Shooting began in 1976 and lasted sixteen months. Over 200 hours of film ended up in the can. The stories that floated around the production have become the stuff of legend, many of which are recounted in the brilliant companion-piece, Hearts of Darkness : A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse (1991), made by Coppola’s wife Eleanor, who courageously documented the entire production on a 16mm camera.

Coppola had an incredible crew working for him, chiefly cinematographer Vittorio Storaro (probably the greatest DOP working at the time), production designer Dean Tavoularis, and editor Walter Murch, who also acted – very importantly - as sound designer. It was Murch who also supervised the exceptional “Redux” extended director’s cut which was released in 2001. The main additions of which are an extension of the Playboy bunnies performance sequence (and later their amorous encounters with Willard’s crew), a lengthy French plantation sequence where Willard and crew are wined and dined by a group of colonialists led by Hubert (Christian Marquand) who expound America’s military blunders and the history of Indochina over Bordeaux and opium, and Willard indulges in a little amorous interlude of his own with the lady of the estate, Roxanne (Aurore Clément).

Carmine Coppola’s amazing score (co-composed with Francis), which utililises the Moog synthesizer to stunning effect (duplicating helicopter blades, and creating a palpable sense of menace and exhilaration) is a key character of the movie, as is the use of The Doors’ The End during the ritualistic, and climatic, killing sequence at movie’s end. A real caribou was slaughtered (as part of native custom) and the effect is truly disturbing.

“I tried to break the spell - the heavy, mute spell of the wilderness - that seemed to draw [Kurtz] to its pitiless breast by the awakening of forgotten and brutal instincts, by the memory of gratified and monstrous passions. This alone, I was convinced, had driven him out to the edge of the forest, to the bush, towards the gleam of fires, the throb of drums, the drone of weird incantations; this alone had beguiled his unlawful soul beyond the bounds of permitted aspirations.”

In a rare-as-hen’s-teeth workprint (which only exists in bootleg form, and clocks in at nearly five hours) there are several notable sequences that were never included in either the original version or the Redux version. The whole movie was set to songs by The Doors, and the entire length of The End is used over the movie’s stunning opening montage sequence which features a Vietnamese prostitute sharing Willard’s bed, then abandoning him to slide into a pitiful haze. Numerous other scenes are longer or have alternated takes, most importantly, the role of Colby (Scott Glenn), the soldier sent in before Willard, who has gone bamboo. He is instrumental in Willard completing his mission, yet inexplicably Coppola decided to leave out a pivotal scene where Colby shoots dead the photojournalist, is subsequently mortally stabbed by Willard, and then encourages Willard to kill Kurtz.

The dawn strike on “Charlie” goes on for nearly half an hour and features a musically evocative “ballet” of the choppers as they fly toward their destination. Another earlier workprint scene has Willard, in his narrow “tiger cage” being carried down to an area in the compound where Kurtz’s native followers, including Colby and Lance (who has completely lost the plot), dance and taunt Willard, and sacrifice a squealing wild pig. The workprint’s assassination sequence – set to the entire length of The Doors’ When the Music is Over - is a very expressionist take, with much ritualistic chanting and dancing that culminates with Willard plunging a spear through a guard and a baby whom the guard has held up in front of him as defence! Willard then enters Kurtz’s sleeping quarters to deliver the final machete blow.

The five-hour workprint is an unbridled mural of sensuous insanity, in all its unwieldy structure, its indulgent, uneven rhythms, it’s bootleg low quality. I seriously question Coppola’s decision for Redux to re-insert the plantation sequence and further scenes involving the Playboy bunnies, and yet leave out the scenes involving Colby, the photojournalist, and Willard’s complete stalking of Kurtz.

“In a war there are many moments for compassion and tender action. There are many moments for ruthless action - what is often called ruthless - what may in many circumstances be only clarity, seeing clearly what there is to be done and doing it, directly, quickly, awake, looking at it.”

Props must go to Dennis Hopper, who plays the photojournalist - “The man is clear in his mind, but his soul is mad”- with deranged glee, and whom was struggling in his own dark wilderness, and deeply grateful to Coppola for offering him the work. Last, but not least, Marlon Brando, who plays Kurtz, and who turned up on set with the utmost arrogance, having not read the script, nor Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (which Coppola had instructed), 40kg overweight, and threatened to quit (and keep his $1m advance). However, his presence in the movie, although often in shadow, can not be undermined by his impudence. Brando provides Apocalypse Now with a true sense of bombastic megalomania.

“The horror! The horror!”

In any form Apocalypse Now is a masterpiece of cinema, a portrait of war as the Devil’s work; a seductive nightmare.