US | 1978 | Directed by Michael Cimino

Logline: Follows a group of close friends’ celebration of a wedding, the damage of war, and finally, a desperate reunion.

This is the story of a group of friends, their happiness and sorrow, their camaraderie and competition, their bond and separation, from the grey steel and concrete protection of a small town to the humid, endless nightmare of the Vietnam War … and back again.

This is the story of how love, hope, and human frailty, amidst the cruelty and violence of combat, irrevocably changed their lives. Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter is a harrowing masterpiece, yet an undeniably beautiful movie, and one of a handful of truly untouchable American movies from the last forty years. Breathtaking as it is heartbreaking.

Michael (Robert De Niro), Steven (John Savage), Nick (Christopher Walken), Stanley (John Cazale), John (George Dzundza), and Axel (Chuck Aspegren) are steel workers and close friends of Russian heritage in the Pennsylvanian township of Clairton at the base of the Appalachian Mountains. It is late fall of 1967. Steven is about to get married to pregnant Angela (Rutanya Alda), and he, Michael and Nick are about to head off to the Vietnam War, so the wedding is both a ceremonial celebration and a farewell.

The narrative is divided into three very distinct acts; the wedding, the war, and the aftermath. The movie begins at dawn with the steel workers finishing their shift and heading straight to Welsh’s Lounge, their friend John’s bar, for pre-wedding drinks. Then it’s time for formalities, a traditional Eastern European wedding, which sees the friends in a rambunctious mood. In the early morning light, still in tuxedos and brandishing beer cans, the five men (minus Steven who’s ensconced in his wedding nuptials) drive up into the mountain range for a deer hunt. Later with the large buck, which Michael has shot and roped to the front of the car, the men arrive back at the bar to enjoy a final carouse.

The second act suddenly throws the audience into the midst of a jungle combat hell as Mike, Steve and Nicky try to survive the horror of the war. They are taken prisoner by the Vietcong, caged below a riverside hut along with other POWs, and forced, one by one, to play Russian Roulette for the perverse amusement of their captors. Steven’s fragile mental state is severely tested, as is Nicky’s endurance level. Michael is the pillar of strength. But the men are eventually separated.

Back home Michael, now a decorated Airborne Ranger, struggles to cope with reintegration. Several years have passed. Steven has also been brought back, but is in hospital and self-imposed seclusion. Nick hasn’t returned from South-East Asia. Linda (Meryl Streep), Nick’s fiancée, seeks comfort with Michael, now that he is home safe (albeit damaged goods). Michael learns from Steven that Nicky is in Saigon, and he is determined to bring him home.

The extraordinary screenplay (which feels like its been lifted from a novel) is from a story outline by Michael Cimino and Deric Washburn (Camino claims to have completely re-written Washburn’s delivered script), and was partly based on a 1975 script called The Man Who Came to Play by Louis Garfinkle and Quinn K. Redeker, about men who travel to Las Vegas to play Russian Roulette. An arbitration dispute prior to the movie’s release secured Garfinkle and Redeker a story credit on the film. With nine nominations, including Best Actor (De Niro), Best Actress (Streep), and Best Cinematography, the movie ultimately won Best Picture, Best Director, Best Editing, Best Supporting Actor (Walken), and Best Sound.

The naturalistic performances are amazing (Walken, De Niro, and Streep – who improvised most of her lines - are revelatory, and it was John Cazale’s last movie as he was suffering from terminal cancer). The storytelling is superb, Vilmos Zsigmond’s cinematography is stunning, especially the scenes of Michael stalking the deer on the mountainside both before and after the war. But it is Cimino’s meticulous attention to production design (the entire movie was shot on location, no big sets were built) that lifts The Deer Hunter’s game considerably. Indeed, this is one of those rare examples of everything coming together magnificently. It is a disquieting tour-de-force, an emotional tour of duty.

It’s a demanding movie, with the wedding and deer hunt taking up nearly an hour of screen time, yet the narrative and pacing flows effortlessly. I first saw the movie on VHS as an impressionable young teen and it left an indelible impact, in visual terms definitely (especially the disturbing Russian Roulette scenes), but more importantly as being one of my very first truly adult movies in terms of the way the narrative unfolded, its tone, the emotional weight. I saw it again a couple more times in the following decades, and then again in recent years (after a long hiatus), and felt the calibre of its storytelling and themes resonated more strongly, more significantly than ever before.

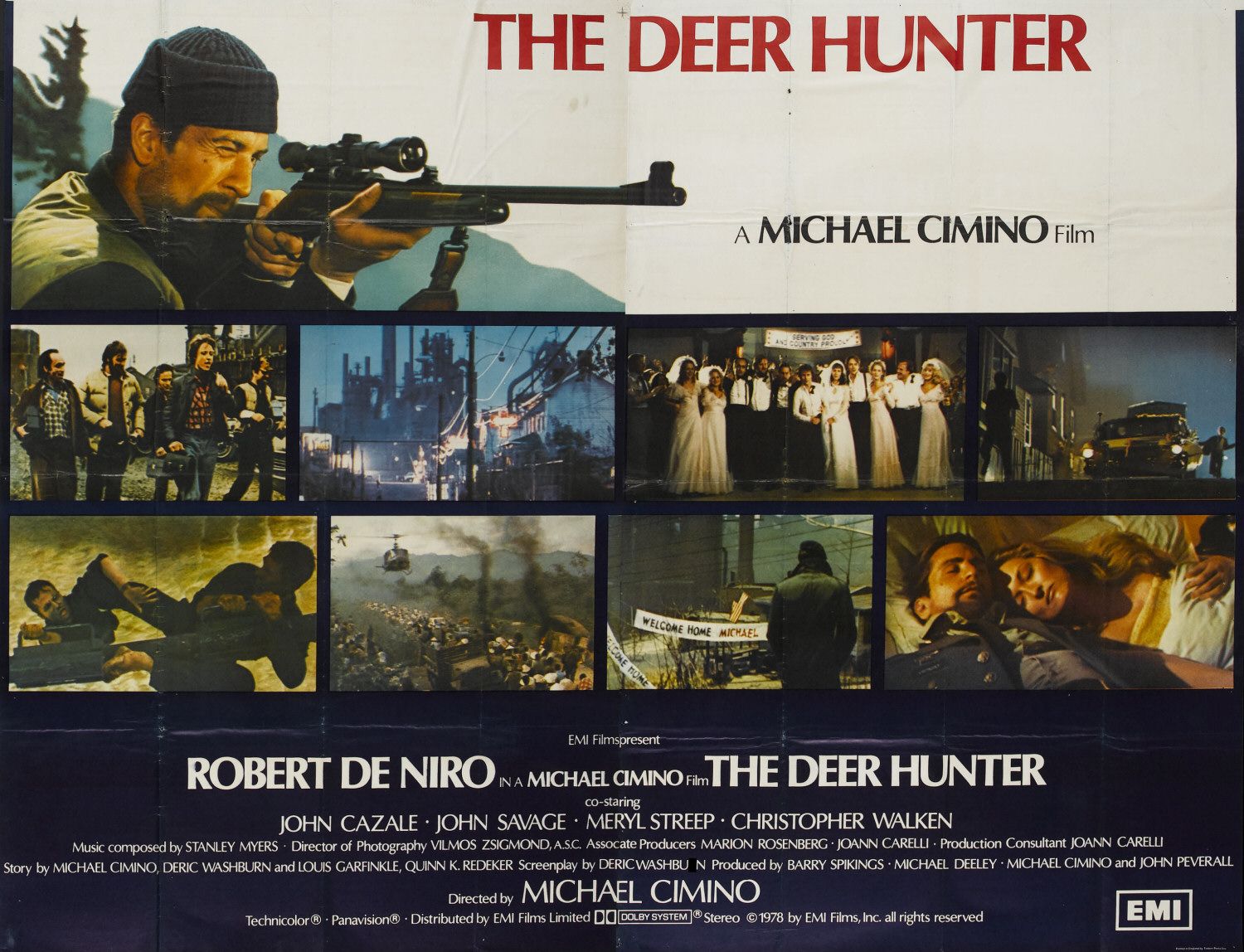

I remember, aged ten, when The Deer Hunter was first released, and seeing the large poster pasted on a street wall, the image of Michael clutching his hunting rifle perched on a rock, the title appearing strangely benevolent, almost arcane, and the censor’s rating, R18, reminding me this was a movie I would not be seeing for quite some time, and wondering to myself, if it’s a war movie, why is it called The Deer Hunter? I guess I’ll understand when I’m grown up. Sure enough, the symbolic importance of Michael as a hunter, as a soldier, as a compassionate, flawed man, really only became clear to me once I had become an adult.

As an adolescent I was impressed by the visceral intensity of the second act (the war), and the tragedy of the third act, but the ramifications of the men’s bond and as individuals, set up in the first act, weren’t as affecting. Seeing it recently again after many years was a profound experience. I’ve changed, the movie hasn’t. The theme song, Stanley Myers’ Cavatina (performed by guitarist John Williams), is still as pivotal and haunting. Some of the movie’s subtleties and nuances that I wasn’t aware of in those earlier viewings now appeared like treasures. The choices we make define who we are, even in the face of terrible odds.

The Deer Hunter grabs you, shakes your hand, spits at you, slaps you hard in the face, embraces you, lets you cry on its shoulder, and finally whispers in your ear, something like … Life is frivolous, life is joyous, life is fragile, life can be bitter, and life can be cruel, but life is vibrant, and life is affirming, and life … life goes on. Even after the nightmare, the inescapable tragedy and loss of war. Life goes on.